Why You’re Failing at Endurance Training: The High Stress Training Epidemic and How to Fix It

Many people push themselves hard in pursuit of fitness gains, but a widespread lack of understanding about endurance training continues to fuel an epidemic of “no pain, no gain” high stress training. While this “give it your all” approach can be beneficial in other areas of life, it is often counterproductive in the endurance training world.

The most common mistake in endurance training is believing that constant, intense effort is necessary to see noticeable long-term fitness gains. This misconception also discourages many sedentary individuals from attempting to build fitness, as they assume the only path to improvement is through relentless, punishing effort. As a result, many people don’t even start, convinced that endurance training is beyond their reach or that they’re simply not “built” for it.

This belief is partly fueled by the over-emphasis on VO2max as the most important measure of a person’s fitness level. Fitness influencers often cite studies where athletes undergo 6-8 weeks of intense interval training, leading to rapid VO2max improvements—sometimes by double-digit percentages. While these results are real, they can be misleading; it’s relatively easy to guide undertrained individuals through a short-term peak in fitness that temporarily boosts VO2max. However, once the intense training phase ends, VO2max typically declines, returning closer to the individual’s previous baseline level.

This leads to athletes believing this is the “best way to train” every week of the year, and that one must keep pushing hard to “maintain fitness” or risk “losing those hard-earned gains.”

However, this approach is only sustainable for a short time before the body breaks down from excessive stress overload. Many people quit at this stage, but some strong-willed individuals can go for months or years beating their body into submission until it finally unravels spectacularly. A temporary peaking phase isn’t a viable year-round strategy for maintaining or improving fitness markers like VO2max; it’s a short-term intervention that merely fuels the “top-end” of fitness, not long-term progression.

This is the number one reason why I have athletes coming to my coaching with heart rates that rapidly elevate the moment they begin an easy jog. Every athlete wants to think they are an exception case and my heart rate is “naturally high”, but they’re usually wrong. What’s going on here? Well, it’s understandable when you consider this perspective: what you reinforce on a consistent basis, is what you will become. This should be common sense, but we don’t often think of endurance training this way.

If you want to create a body that is under chronic stress overload, then simply apply constant high-stress training.

A high-stress conditioned athlete usually goes through the following journey:

- 1. Performance will rapidly increase and temporarily peak fitness (making this style of training highly seductive at first – because an athlete sees those rapid tasty gains).

- 2. Plateau period – often leading to athlete doubling down and putting in even more work.

- 3. Overtraining syndrome (metabolic burnout) or injury with fitness regression and sometimes damaging consequences.

- 4. Long period of rest. Exhaustion, depression, health setbacks. Frustration. Lost fitness.

- 5. Eventual return to activity as the need to exercise for health increases the more time the athlete is sedentary. Repeat the process again.

It’s a sad journey that many athletes repeat for years and years on end. Never really increasing their fitness from one cycle to the next, and each time their overall health worsens. What really should happen is you get fitter every year that you train, while your level of fatigue stays low, and your health is never compromised but improved from exercise. And even if you have short breaks from training due to personal circumstances or injury, your base fitness should never decline significantly at any portion of the journey – even with months (or sometimes years) off of training.

Ultimately, fitness gains from high stress training don’t stick. They are fast to achieve and fast to lose. Fitness gains from low stress aerobic base training stick for many years. They are slow to develop but slow to lose. Yes, you will lose “some” fitness by not training for a year or two, but if you’ve remained overall healthy enough, with just 1-2 months of training, most of your previously built base fitness will come back online.

It’s essential to understand the type of fitness you’re aiming to build, as not all “fitness” is the same. For example, when I raced competitive stair races, these events often attracted muscular, barrel-legged gym focused athletes who were exceptionally trained through a steady diet of high-intensity intervals. Yet, in a 6-8 minute stair climb, lean endurance runners would consistently dominate—and by a wide margin. While I might struggle to beat one of these gym athletes in a sprint; over a 6-minute race, I’d win by several minutes, sometimes by a lot, as these athletes would quickly burn out after a few flights of stairs.

Competitive efforts beyond 1-2 minutes still require significant aerobic endurance as much as power and speed. Although these athletes focused on what’s typically considered “VO2max training,” they still lacked any well-conditioned endurance base. High intensity trainers are fast and powerful, but they have no stamina.

VO2max is an important indicator of a person’s health and fitness, but it’s only one of many components of overall fitness. It measures the maximum rate at which an individual can consume oxygen during intense exercise. However, a high VO2max doesn’t necessarily equate to exceptional endurance performance, as endurance also depends on factors like lactate threshold, oxygen transport efficiency, mitochondrial and capillary density, and much more.

While VO2max reflects aerobic capacity, an athlete’s ability to sustain a high percentage of their VO2max over time (such as at lactate threshold) and efficiently utilize energy sources is what ultimately determines endurance success.

Many of these additional attributes help elevate VO2max not just temporarily, but in a way that builds that “Permanent Fitness” I discussed earlier. If interval training and constant hard effort were all that mattered, it would be the sole focus of the world’s top athletes. However, the reality is starkly different. Most elite athletes spend 80-90% of their training at relatively easy intensities, even if they specialize in short races like the 1500m, which lasts less than 4 minutes. It’s the accumulation of a lot of easy training that builds movement economy and metabolic improvements that allow significantly increased performance and stamina.

By building a highly conditioned aerobic base, athletes can further elevate their VO2max before peaking for goal events with high intensity training. The stronger this aerobic foundation, the closer VO2max approaches its genetic ceiling over time. But even at that ceiling, fitness can still improve due to other trainable aspects of endurance beyond VO2max.

Intense workouts in every session can seem appealing, especially to time-crunched athletes who feel that unless they’re breathing hard, they’re not making meaningful progress and are wasting valuable time. While common, this mindset often hinders progress. The reason why is: metabolic stress and stress based nervous system conditioning.

Each person’s capacity to handle training stress varies. For those less trained, the body manages stress less efficiently and requires more time to recover between intense training sessions. Yet many people don’t allow their bodies the necessary rest to handle this level of strain, often stepping into another hard session well before the body is ready for it.

At its core, fitness reflects metabolic efficiency. As the metabolism becomes more efficient, the body can manage greater training loads with less strain, enhancing stamina, endurance, and speed of recovery over time.

Metabolic Fitness: What Endurance Really Is

Metabolic fitness refers to the body’s ability to efficiently convert energy from the food you eat into energy your body can utilise to fuel performance. Good metabolic fitness is foundational for athletic performance, overall health, and longevity.

Key components of metabolic fitness include:

- Mitochondrial Health: Mitochondria, the “powerhouses” of cells, are responsible for producing ATP, the body’s primary energy currency. Healthy, well-developed mitochondria improve endurance, allowing athletes to sustain activity for longer periods without fatigue.

- Insulin Sensitivity: Metabolic fitness includes the ability to use insulin effectively, which helps in controlling blood sugar levels. High insulin sensitivity means the body can use blood glucose more effectively, reducing the risk of energy crashes and promoting better energy balance during training.

- Fat Oxidation Capacity: Individuals with good metabolic fitness can efficiently burn fat as a fuel source, especially at lower intensities, preserving glycogen (stored carbohydrates) for more intense efforts. This capacity is especially valuable for endurance athletes, as it allows them to sustain prolonged exercise without exhausting glycogen stores.

- Lactate Threshold and Clearance: Metabolic fitness encompasses the ability to work at higher intensities without rapidly accumulating lactate. When lactate does accumulate, efficient clearance helps prevent the "burn" feeling and allows sustained efforts without premature fatigue, redirecting the lactate to be used as additional fuel.

- Hormetic Adaptation: A well-regulated metabolism responds positively to manageable levels of training stress, strengthening the body’s capacity to adapt. This adaptability includes improvements in cardiovascular function, recovery speed, and resilience to physical stress.

Building metabolic fitness is a gradual process that involves balanced, lower-intensity training and a lifestyle that prioritizes nutrition, stress management, and recovery. As metabolic fitness improves, the body becomes better at handling larger training loads with less strain, supporting long-term fitness gains and reducing injury risk.

One major component of what endurance is, is how well developed your mitochondria factories are – the powerhouses of the cell – the organelles that create ATP the fuel that feeds your muscles performance. Not your lung capacity, which is genetically set and unchangeable from physical training.

Pushing yourself hard doesn’t actually increase your lung capacity. Our lungs are already naturally big enough to breathe in all the oxygen we will ever need. Instead, training enhances your body’s efficiency in being able to extract oxygen from the air and transport it through energy pathways to your cells. Training improves multiple bottlenecks in these pathways. In other words, most people are inefficient at utilising all the oxygen they breathe in, which is why the body forces an increase in breath rate to meet the demands of hard exercise.

This doesn’t mean high intensity hard training is useless, it’s very much crucial to the endurance equation, but it needs to be carefully applied in strategic periods of the training cycle; not utilised for the bulk of training time.

For most athletes – even those time-crunched ones - they are far better served spending most of their training time on optimizing training to support improved metabolic development. Guess what kills metabolic health? Oxidative Stress! But guess what helps to stimulate your metabolism to be stronger …also Oxidative Stress! Confused yet!?

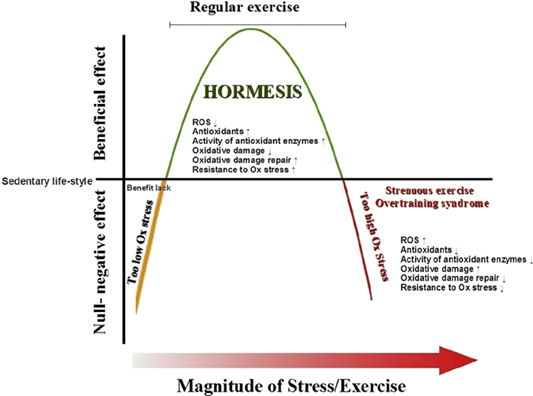

Let’s unravel this some more. The body isn’t a machine that constantly delivers more simply because it’s asked for more. It can only manage a finite level of training and racing stress, akin to a bell curve with a delicate balance between too little and too much. This is known as Hormetic Stress or Hormesis.

Hormesis is the optimal level of stress that challenges your body without causing excessive fatigue or negative effects, allowing it to allocate resources towards building a resilient cellular environment and enhancing metabolic fitness.

Any training you do causes a certain level of stress to the body, which is applied with the hope the body will adapt to better handle that stress in the future. This is why recovery is so crucial: it's when your body adapts and strengthens in response to training. Without adequate rest, fitness doesn’t improve; instead, you either maintain your current level or risk regressing, neither of which is ideal. Your fitness and endurance increases while you rest not during training. Training is just the trigger to initiate an adaptation process, but whether you hit the bullseye or not depends on what comes after it. More training too soon will derail the adaptation, but if the training applied remains within the hormesis zone, then it can have an added benefit.

The bottom line is this: The harder or more intensely you train, the more recovery you’ll need afterward. Training at high stress every day (or most days) leads to accumulating a “stress debt” that will eventually need to be repaid. There are diminishing returns for hard training when we factor stress into the equation.

Careful training within the hormetic zone means your body is neither weakened from a lack of stress nor overwhelmed by toxic stress that triggers the body’s emergency “fight or flight” response. If you go beyond hormesis, you start to create significant levels of oxidative damage that actually impairs your endurance. It not only prevents new endurance growth, but it also begins to rob you of your pre-existing endurance by damaging healthy mitochondria.

True fitness gains occur in the hormesis zone of the bell curve, which varies for each individual due to unique factors. Thus, effective training involves finding the right balance to promote adaptation without crossing into counterproductive stress. How we find this in training, requires listening to the signals the body gives following training, combined with the athletic history of the individual. Getting this balance right is the most important factor in endurance training, and the boundaries constantly shift, making it a precarious slope for unknowledgeable athletes.

In simplest terms, the most meaningful gains come from long-term consistency in low-stress training volume, supported by good metabolic health through diet and exercise, and a lifestyle that balances stress and rest—enhanced by strategic periods of peaking training.

It’s true that the healthier an athlete is metabolically, the better they will perform over the long term. While some athletes can push themselves to achieve short-term success through sheer force, this approach has a clear expiration date. Performance-enhancing drugs may extend this timeline temporarily, but they come with severe long-term consequences for metabolic health.

Another major issue beyond overtraining is injury, a common challenge, especially for heavier runners. Many people adopt an all-or-nothing approach early in their running journey, going from years of a sedentary lifestyle to suddenly attempting a sustained run on their first training day. Jumping from no exercise to intense running is another high-stress event for the body, imposing significant strain on both biomechanics and metabolic systems.

While some manage it, they often struggle to walk for days afterward, experiencing aches and joint pain, particularly in the knees. This is where the myth that “running is bad for your knees” originates. Many new runners stop at the first sign of knee pain, fearing they’ll harm their bodies permanently. Most beginners are better served at mastering walking and hiking with small spurts of running interlaced in, rather than trying to run straight away.

High stress also creates elevated tension in your neuromuscular system, significantly increasing the risk of injuries. By learning to relax your nervous system, you enhance your ability to stay loose and flexible during impact, rather than stiffening up. This approach is equally important outside of training, particularly when focusing on strength, mobility, and techniques for releasing muscular tension, such as foam rolling.

Sadly, high stress training can also lead to cardiac events, where overexertion, often combined with a history of pushing too hard, or chronic stress and high blood pressure, results in a heart attack. This risk is heightened by neglecting essential habits like proper warm-ups, managing lifestyle stress and good nutrition habits.

Inadequate warm-ups—a widespread issue in endurance sports—are another high-stress event that can significantly increase the risk of cardiac events, especially when athletes jump straight into high-speed activity without easing in.

Warming up is a cornerstone of my training approach. It’s crucial to ease into exercise gradually, allowing your body to adapt and open up to increased performance over the first 15-20 minutes of movement letting your breathing be your guide. Also, an effective warm-up will tell you whether today is a good day to push into high intensity training or not. High energy during a warmup is a positive signal for pushing hard today, but a poor feeling may signal additional recovery is needed.

The kindest approach to your body is about learning to respect the body with careful stress-based adaptations, which is the safest approach to training that regulates the nervous systems reaction to increase training volumes without significant stress impact.

Knowing is one thing, but doing it right, is far more difficult to achieve. The truth is that you don’t need to punish yourself to make progress. This should be welcome news for many people coming off the no pain, no gain express.

My “Blitz” Training Method: Becoming an Endurance Beast

Blitz sounds like a cool name for a high intensity training method, but its my answer to correcting the problems that emerge from a body conditioned to high-stress training. It is an acronym for “Breathe Lightly into the Zone” training, which doesn’t many any sense yet, but it will by the end of this article.

For now, it’s important to understand that low stress training optimises metabolic health in a way that delivers sustainable long-term performance results. In Blitz, I help you to retrain your nervous system to downregulate the chronic stress response conditioning from years of poor high stress training habits. This then allows the repair crews to come in and rebuild your damaged mitochondria so they can produce ATP more effectively again and teaches your nervous system that it doesn’t need to start hyper activated to protect your health.

Improving mitochondrial health and improving endurance performance go hand in hand, and therefore, health and longevity is a significant positive byproduct of this training approach.

Putting Blitz it Into Practice

I live in Vancouver, Canada, and here there is a famous climb called the Grouse Grind (known as nature’s stairmaster) an uphill only 2.5km trail that ascends 800 meters (2600ft) of vertical climb with a gondola ride down from the top. Because of the gondola, it’s a very popular trail with tourists, beginners, and elite athletes alike all coming together as a melting pot of sweat and Lululemon active wear (another Vancouver icon).

Almost everyone climbing this trail is pushing themselves hard and you can hear the breathing of everyone around you. Most people have a love-hate relationship with the trail, but that’s because it’s hard - for some very hard - to get to the top. For elites its 25-30 minutes pushing hard but for undertrained individuals it can take up to 2-3 hours to finish. Its not uncommon for regulars to come to the trail multiple times a week and push it hard.

Because it’s the local fitness climb, most of everyone who tackles it pushes themselves on the climb to get a “good workout”.

In June 2024, I equalled the record for the most climbs of this trail in one day during the Multi Grouse Grind Challenge (known also just as the Multigrind), the official event held in June each year to crown the best multigrinder! I successfully climbed the Grouse Grind 19 times in 19 hours for 15000m (50000ft) of vertical ascent. See article here.

When some local people hear of this achievement it sends a shockwave through their brain, like its almost too astonishing to comprehend for those who find just one ascent a brutal proposition. The first reaction is natural, but incompletely inaccurate, they assume that I am sucker for brutal pain, and I’m “not human.”

However, I feel human, and I have my own issues with stress, laziness, fatigue, injury and illness like everyone else. In fact, the week before the event I was really sick, and I was still feeling a little congested during the event. It obviously, didn’t affect me in the end, but I wouldn’t say I felt 100% either. In the lead up, I also spent more than two years out of regular training from injury and was only able to train consistently starting 10 weeks prior to the event. But what I did know, was how to best train and maximise my time to prepare for the event. I also had the experience of having done the event before in 2019. This was enough to edge me to victory over a couple of other strong competitors, and is a clear demonstration of that “permanent fitness” notion I addressed in the opening.

After two years off regular training, I had no right to equal the record and win this event with just ten weeks of focused training, but I did it.

I found the day difficult (obviously), and right at my limit to pull off, but for the most part, I wasn’t really suffering. I was tired from the effort and long day, but I also felt largely relaxed for most of the day, and in a meditative “in the zone” state of feeling. This is something I specifically trained for and conditioned into my physiology during those ten weeks of training.

Remember what I said about “what you train for, is what you become”. Rather than conditioning stress, I conditioned the total opposite. In a 19-hour event, I wanted my body to be as low stress, energy efficient as possible while climbing up this steep trail.

To train for this achievement, I did no high stress training at all other than a couple of sessions to see where my time-trial time compared with previous bests. My personal best on the Grouse Grind is 29:35, but I was time-trialling at 36 minutes after two years away. Still great, but 20% down on my best. Getting to sub-30 power, didn’t matter to win this event, but what I did need was to get as energy efficient as possible in a sub 50-minute effort.

All my training was for me “easy” in what would generally be considered Zone 1 in a five-zone intensity model. I had long training days that were tough, but they were easy in terms of applied stress.

I purposefully and specifically trained my body to climb as fast as possible while remaining in a very low stress state of being, practicing every session on the mountain with the exact state of feeling I wanted to feel throughout the event. I wanted to feel in the zone, so I trained myself to be in the zone in every single training session.

When I began my first week of training, I felt like competing at the front in the Multigrind was going to be impossible. To match the existing record of 19 climbs would require climbing the Grind no slower than 48-49 minutes on every climb just in time to not miss the tram down (that left every 10 minutes). Missing a tram would doom the possibility of making it to 19 and require a significantly faster 38-39 minute climb to get back on pace.

During training, I would often climb the trail 3-4 times in the morning over about 5 hours of training time, and I’d often come home in the afternoon feeling like I hadn’t trained at all, such was the minimal impact that the training had on my energy reserves. If I had done 3-4 climbs in a high stress state, I would probably need a week to recover from that kind of session. Instead, I was able to do 3-4 climbs most weekdays, and I would usually take two full days off in between for recovery on weekends. If I needed more rest, I took it. I had a plan I worked off, but my body’s feeling each day held higher priority over the plan.

One noticeable aspect of my training was that, while climbing the trail, you wouldn’t hear my breathing. I often startled people as I passed by, as they couldn’t hear me approaching like they would with others. I focused consciously on managing my internal stress and using my breath to downregulate my nervous system. Whenever my breathing began to feel out of control, I would simply stop, let everything settle, and then continue. There was no ego involved—no concern about specific times for each climb. My only goal was to practice the internal state I want to sustain.

In the first week, my Grind time was 65 minutes using this relaxed approached. But by the end of the 10-week training block, my pace at this same feeling had increased to a 45-minute climb time with barely any breathing sound. I didn’t need to do any high intensity training to improve my speed, it was just increasing efficiency from consistent repetition.

By training my body’s efficiency at relaxing into an effort I accessed my ability to perform at a fast pace or level for longer, with much more energy efficiency. Remember that internal stress is a heavy energy sink, that’s why you always feel so depleted when you’re under high stress from any area in life. If you can make as much of your training as low stress as possible then this is how you can develop endurance in a healthy and sustainable way.

The Zone – The “Mythical State of Performance” That You Should Actually Condition Most Training Days

In our modern social media reality, epic feats of endurance are celebrated and cheered on. Think Kilian Jornet and his Alpine Connections project, where he astonishingly (but predictably) moved through the alps monotonously with his trademark calm composure for three weeks straight (on barely any sleep), to summit all 52 4000m+ peaks in the alps during August 2024.

Jornet is someone who keeps delivering, despite advancing years, and now also having small children at home. In 2024, he broke his record time at Sierre Zinal – a high-speed alpine race that attracts the fastest high-performance mountain runners in the world. Jornet won it for the 10th time, and the fastest run he’s ever completed on the course. This was a staggering achievement for an athlete at his stage of life and career.

Perhaps the biggest reason why he keeps delivering, is he practices the fundamental principles I am talking about, most primarily training for enjoyment and relaxation in the moment and balancing his hard sessions with appropriate rest. I’ve watched videos of him training and he is locked into the zone. It's not just fundamental to his training, its fundamental to who he is as a person, so integrated into this personality and lifestyle, that it’s just a perfect storm for high level performance.

His is just one example of many countless feats of endurance we are lucky to bear witness too in the modern era of performance. Athletes are getting fitter than they ever have been before, and as a result, pulling off bigger and bigger monumental achievements that boggle the mind. Part of this is improved training, part of it is improved nutrition, and part of it is lifestyle orientated. Many elite athletes no longer party it up like their contemporaries, getting to bed early and sacrificing nothing in the relentless pursuit of recovery efficiency. It all matters at the very top of the sport, now more than ever before.

Endurance athletes are well renowned for their mental toughness, their ability to endure hours of pain, and to push through adversity where most others would stop. Obviously, Jornet went through a lot of stress in his Alpine Connections performance, but his body was highly trained to handle that stress load, absorb and buffer it, and constantly deliver day after day.

This recovery efficiency not only helps him move from one race or project to the next one relatively quickly, but it also means he can handle more training volume and intensity each week in training than the average person. A training session that would destroy a recreational athlete’s energy levels for a week or two; Jornet can recover from it overnight. It took him years to build to this level of efficiency. There is no shortcut to get there.

Kilian at 37 years old (at the time of writing this) effectively started training at 3 years old due to his parents work as mountain guides, building on each of those 34 years of training with a little more volume each year until he reached a peak of around 1200 training hours per year. Now we works on refining his training process to the finest degree. So even at 37 years old he’s still performing better than he ever has because he is still refining his training process. There is a lesson in this for all of us. Even after 34 years of training, Jornet still believes there is room for improvement in his process.

Jornet has turned recovery into an art form. He no longer takes full rest days, opting instead for light active recovery to promote nutrient flow and aid recovery in his tired body. However, this approach isn’t suitable for every athlete. With 34 years of training, Jornet has developed exceptional resiliency in his muscles, ligaments, and tendons. In contrast, many developing athletes require full rest days to allow their bodies to repair microdamage caused by impact loading. At Jornet’s level, his body is so well-conditioned and efficient at handling training stress that he can sustain higher weekly training volumes without risking significant chronic stress or overload.

His adaptations are rapid, and his body is so efficient that to continue improving, he must sustain very high training volumes each week. However, this doesn’t mean increasing high-stress levels in his training. This efficiency isn’t a genetic gift unique to him—it’s a completely trainable component developed through years of disciplined practice and carefully planned progressions.

It’s easy to watch as an outsider or new athlete to the sport, that significant effort needs to be put in to train for his accomplishments. And you’re not wrong there. A lot of effort does go in, but let’s not confuse volume with intensity, or low stress vs high stress.

Jornet is highly disciplined and incorporates intensity training into his routine, but it is carefully calibrated against the enormous, metabolically efficient aerobic base he built over years of development. This base, established through a multi-year progression of steadily increasing low-stress training volume, is the foundation of his ability to mitigate chronic stress and avoid the overtraining syndromes that hinder many endurance athletes.

Much of Jornet’s training is conducted in a state of complete relaxation, resembling a form of active meditation. I have observed he also deliberately trains himself to be in the “Zone” by spending the majority of his training time in that calm, controlled state.

When you think of the zone, you might think of Michael Jordan in his prime, mesmerizing opponents and the audience alike, as he rises through the blocks to slam dunk a basketball with effortless grandeur, or Eliud Kipchoge as he breaks the 2-hour barrier in the Marathon with a stride that never breaks its cadence, at speeds that most people couldn’t run for more than a few seconds.

It's very much a state of mind that has a strong nervous system component to it.

We all instinctively understand that achieving the “Zone” is key for athletes to reach historic levels of performance. Rarely do we witness pinnacle achievements made in a compromised, high-stress state. However, in feats of endurance, exhaustion eventually takes its toll. As an athlete nears their limit, the effortless brilliance of the Zone begins to fade—graceful movement shifts to flailing limbs, a hunched posture, and uncontrolled breathing. Yet, even to approach such extraordinary accomplishments, an athlete must find the Zone, sustain it for as long as possible, and then endure the final stretch, hanging on until the effort is complete.

In the Multi Grouse Grind Challenge, I felt in the zone for the first 75% of the event, and then it was just hanging on for the final 25%. With more training I could further increase the time I could stay in the zone for, and also the speed I can climb at in this zone state. Therefore, the limit of my potential ceiling of performance has still not been reached. Far from it.

The key to understand about being in the "Zone" is that it's not a magical, mythical or mystical state reserved for elite athletes, nor does it spontaneously appear after years of intense training, just emerging once in a blue moon on race day. Instead, you must train deliberately to become everything the zone encompasses when it counts—especially as you start getting tired. Training must prepare you specifically for what you will encounter in a race, so if you don’t train for the zone, its most likely you’re not going to miraculously find it in a race either.

Ultimately, you need to be training specifically to become what you aim to be. Logically, you can't enter and maintain the zone if you're in a state of high or prolonged stress, because high stress is the anthesis to what the zone is. The Zone is a highly attenuated performance state characterised by low stress and full control over one’s physiology. When the nervous system becomes stressed, the Zone vanishes along with it. However, the stronger the foundation you build to support the Zone, the better you can handle temporary spikes in stress while maintaining that optimal state more effectively than others.

Furthermore, training in the zone is the most accurate way to keep yourself in the center of the hormetic stress bell curve discussed in the introduction. If you’re in the Zone, you’re truly balancing the stress balance equation, and from there you can begin to push the volume and speed carefully that will elevate your endurance, breaking through plateaus, and onto that next level of higher performance.

Remember that endurance training is very much akin to a martial art. It’s a state of mind and mental activity that integrates entirely with your nervous system and ability to stay grounded into your self and your surroundings. Treat your easy training days like a meditation, pay attention to your breathing, relax your breathing, and emphasize full focus and control over your training practice.

Don’t be afraid to stop momentarily to let things calm down and relaxed before pressing on whenever you feel like you’ve stepped out of the zone into the high stress state. Do this for the bulk of training and you will go a long way, and it will make those peaking phases way more effective prior to goal events and races.

The glaring reality is this: Most recreational athletes do far more high stress training than successful elite athletes do. This is why you can’t copy the training methods of elite athletes and believe this will make you like them. You might be copying a workout structure, but are you embodying the state of mind, state of feeling, that the elite athlete is feeling in the workout? Probably not, its likely you’re overextending yourself and heading down the backside of the hormesis curve. Endurance is not about pushing yourself so hard with the hope that it makes you better, without fully understanding the martial art that successful endurance training entails.

This Won’t Work For Me: The Busy Recreationalist

I know what you’re thinking. This is all understandable, but I don’t have time to train 20-30 hours a week for 30 years straight: Noted! With the Multigrind training I did I was often training five hours a day, and this was very much needed to successfully build the type of endurance required for a 20 hour ultra-endurance event.

My advice to those with less time or who are not focusing on longer events. It doesn’t matter, and you shouldn’t compare yourself to others. Don’t let your lack of available time stand in your way of mastering the martial art of endurance training.

Even if your goal is in shorter, faster races, no one can go hours and hours at their absolute limit – as humans we can only push at our lactate threshold (a common training science term for a sustainable hard race effort) for around 1-2 hours. Anything longer, requires a sub-threshold pacing strategy. Even in races of 30 minutes to 1 hour, it still requires a careful pacing strategy of pushing right up the red line or edge, but still relaxing into the hard effort. If you’re not relaxed during a hard effort, you’re not going to access the deeper layers of your highest performance potential.

You can get started tomorrow, even with as little as a few hours a week training in a more productive low stress way that will steadily improve your endurance off of today’s baseline.

Are you making today a little bit better than yesterday?

You still have a lifetime ahead of you and its never too late to get started.

And most of all, you need to remember that you won’t build fitness in times of high stress. Stress could come from anywhere, from overtraining, from home, work, and even mental states of mind. Exercise is one of the greatest tools we have to destress the body, but only if we do it in a way that doesn’t add to our tank of internal stress.

When your body is overstressed it cannot deploy resources to “upgrade your physiology” to make fitness improvements. Relaxed training can help to get your stress baseline to lower to healthy levels and from there you can implement appropriate levels of hormesis to begin improving endurance again. This is why walking is actually the greatest form of exercise when you are facing high stress. Its naturally low stress and its repetitive function quickly downregulates the nervous system. Get out into nature and walk, and once your vitality returns, you can then progress to some light running if you want.

It’s important to build on this philosophy of “escape” from the high stress lives we live. If you’re going for a run, make it your mission to instead treat the run like a relaxation meditation, rather than a “hard push to build fitness”. Repeat “relax” in your mind like a mantra, to condition your nervous system to downregulate when you move. Condition your body over time to slowly move faster in this downregulated state. Embody what you want to become in every moment.

As you get efficient at moving in a low stress manner, and once you have mastered that and conditioned this response in your physiology, then you’re ready to take the next step to some more advanced training to access your highest levels of performance.

The adventure angle of endurance sports and getting into nature, is perhaps its biggest appeal. As human beings, adventure is in our nature, stoking our primal sensations for a few hours each week to restore some life balance to those other hours at home and work. Do as much of your training in a low stress environment as you can. Stay away from loud music to distract your mind away from the martial art of the training process. Train to silence if you can and deepen your grounding into your body and your natural environment as much as possible. Also stay away from stimulants like caffeine that make it hard to relax, to downregulate the nerves, and find that feeling of being in the “zone” in your regular training.

I do all my racing caffeine free and I don’t listen to music to distract myself either. I truly look forward to my training time each day as my “me time”. Everything I do supports my metabolic health, my mental grounding, and a positive relationship with training and movement.

My Blitz Training method approach is designed to shift your mental understanding to how training should be approached, and you won’t argue with the results once you find it for yourself. Please get in contact with me and consider me as your coach if you really want to access the next level of performance and health in yourself by learning the core methods and principles of my Blitz endurance training approach.

Coaching merges art and science, especially when it comes to stress management for athletes. My goal is to help an athlete stay in hormesis as consistently as possible, and I do that by teaching my athletes to stay in the zone through controlled regulated breathing, patience, education and grounded focused mindsets.

Learn more about what I offer for Endurance Coaching at this link: Couch to the Summit Performance Coaching

Please also check out my video of Racing Matterhorn Ultraks where you can see how relaxed I am when racing a hard high alpine race embodying the principles of my Blitz approach - all while filming and having fun!